Of the notable baths of Budapest you might have missed Kiraly. It’s not Széchenyi with its old men playing chess in vast steaming outdoor pools behind fine art nouveau towers. Nor Gellert, the textbook Central European indoor bath. Kiraly is older and more mysterious. From what I could tell its roots go back to the 16th century, when Ottoman rule swept in new influences like, well, bathing. It may be that baths like that date back further, to ancient Constantinople – the shape of the Kiraly baths brings to mind Byzantine churches.

The Kiraly furdo looks by some distance to be the oldest building around it at the foot of the hilly core of old Buda. Imagining the Danube in its pre-embanked state flowing through Budapest it would have been closer to the shoreline. The entrance and changing area are modern, with the slightly bewildering list of prices and options found at all of Budapest’s baths giving rise to mild panic, amplified by the oddness of being in something like a bathhouse, with pretty much no idea what you’re doing.

Anyway, in I went and after handing over several payments for a few different things (a cabin, a locker and a towel), one of which I did not have any need for, I found myself climbing the stairs to the changing area. The baths are very clean and very well set up, with electronic tags to close and lock the door of the cabin. There is therefore no need for a locker. There is, you filthy Anglo-Saxon, a need to wash thoroughly before entering the pools and steam rooms. Having done so, I made my way through each one in probably the wrong order.

The main pool appeared to be a social space, with couples old and young, groups of girls and lone males sticking to edges, only occasionally breaking out into the middle space. I like seeking the cooler pot for a spot of invigoration before returning to the warmth. Eventually I found my way into the steamiest of the steam rooms, with a thick fug of hot damp air covering everything including those breathing deeply inside. It was set in one of the pointed corners of the baths main building. Above it were thick glass tiles letting in the afternoon light, playing games with the steam and the darkness. I sat back and thought of the Ottoman Empire, of Patrick Leigh Fermor’s short stay in Buda, and then wondered if I’d sat in there long enough to feel like I had done the whole bath thing. Concluding I had, I left and continued to stomp around the city until it was time to catch that evening’s sleeper train to Munich.

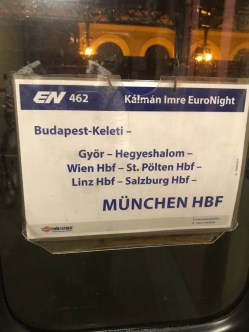

At Keleti Station, with its statues of James Watt and George Stephenson, the night train to Bucharest was just leaving. Shortly after a train to Kiev headed out, then another to Prague. This parade of mighty journeys was soon joined by ours, named after Hungarian composer Imre Kalman, heading first to Vienna, then splitting in Salzburg with one half bound for Zurich and the other for Munich. Each one left 20 minutes late.

As ever when sharing a couchette with strangers there was no doubting the blind was going straight down and the heat straight up. No-one, for reasons I don’t understand, ever wants to look out the window of a night train. I twiddled the heat down and didn’t argue on the latter. It had been a long and cold day and I was very tired, so with earplugs was not troubled by the man and the woman below me who for complete strangers seemed to get on very well. How well exactly I am not sure, but they were still jabbering away at 4am when we pulled out of Salzburg. Plenty of additional passengers had boarded at Vienna, now the hub of Europe’s sleeper network.

The whole slightly ramshackle night train thing suits being moved deeper into Europe. But people still believe. We trundled back west through the night across rivers and through cities I’d rather have stopped at but will settle for having passed for now.